WRITING 2017 International Calligraphy Symposium

November 2 - 8, 2017

» WRITING 2017 Symposium Class Report

» WRITING 2017 Symposium Brochure

» WRITING 2017 Symposium Registration

WRITING 2017 International Calligraphy Symposium

International Calligraphy Symposium is an bi-annual event organized by the International Research Centre for Calligraphy (IRCC) at the University of Sunderland, UK.

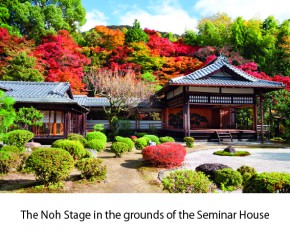

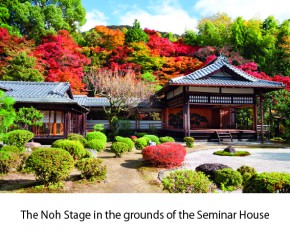

We are delighted to announce our next symposium will be held in the picturesque Kansai Seminar House in Kyoto, from Thursday, November 2nd to Wednesday, 8th, 2017.

We are delighted to announce our next symposium will be held in the picturesque Kansai Seminar House in Kyoto, from Thursday, November 2nd to Wednesday, 8th, 2017.

This is truly an international calligraphy event. For the first time, the NPO Japan Letter Arts Forum (J-LAF, Tokyo, Japan) and IRCC are working closely together to deliver this symposium to you.

The theme this year is to explore the potential of the brush. We have on offer a range of exciting workshops that would benefit and enrich calligraphers of all levels and abilities. The tranquil and beautiful environment will encourage a more contemplative approach to your work. Classes will finish by early afternoon to allow participants to work on their own in the calligraphy studio. Optional trips to local sights are also available.

Kyoto is the ancient capital of Japan and it is one of the most historic and beautiful cities in the world. Its heritage and tradition are a delight to the senses. The environment, people and its culture would certainly make this event an unforgettable experience for everyone.

■Classes

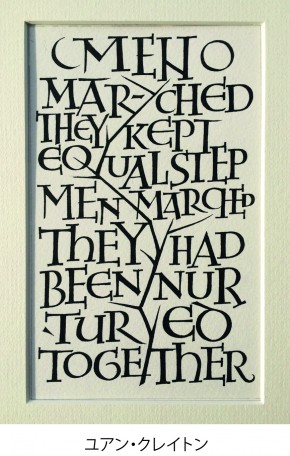

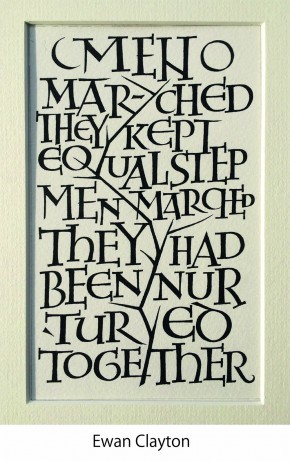

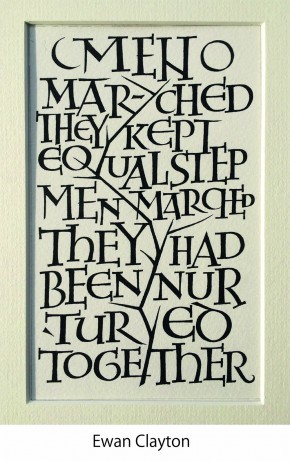

EWAN CLAYTON ‘The Painted Letter’ fully booked

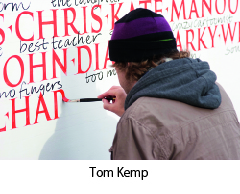

TOM KEMP ‘On the Edge of the Brush’

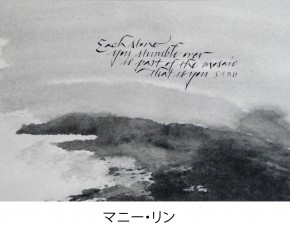

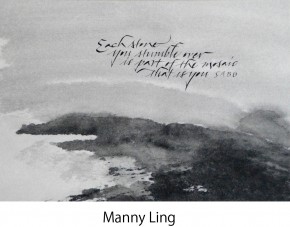

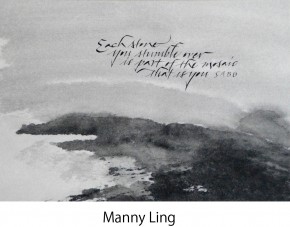

MANNY LING ‘Crossing Boundaries’

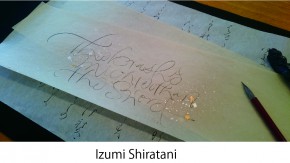

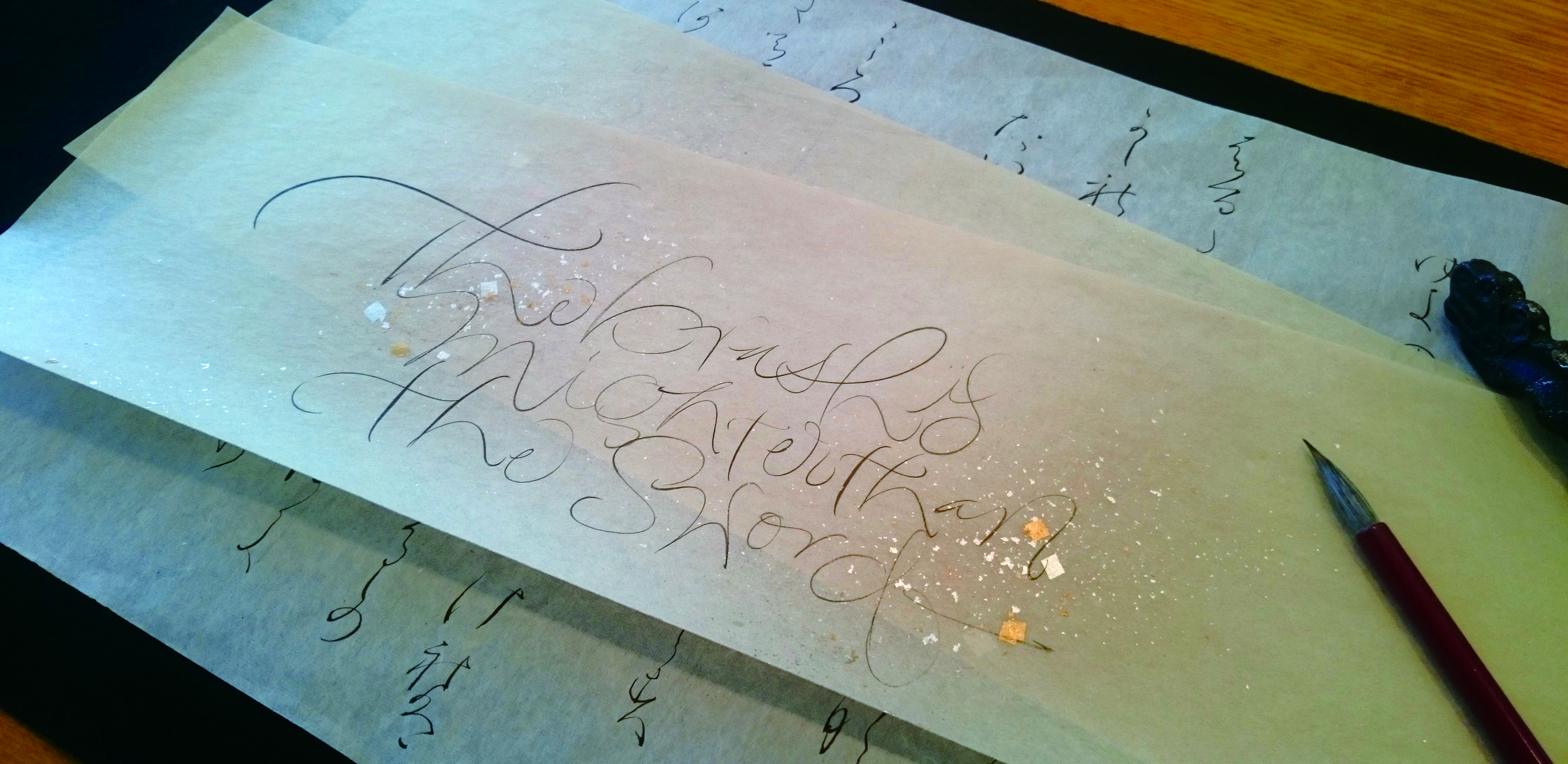

IZUMI SHIRATANI ‘Finding Your Brush Lines’

■Date

Thursday, November 2nd - Wednesday, 8th, 2017

■Venue

Kansai Seminar House, Kyoto Japan

further information (pdf)

WRITING 2017 KYOTO

■Registration

Registration will start from March 1st at 22:00 Japan time.

further information